Have you ever been to a presidential library? Each site is located in the home state of the president and they are maintained by the National Archives and Records Administration. The libraries contain exhibits, historical documents, and relics that reveal aspects of a former president’s personal life and professional career. Taken all together, the contents of the library are meant to give a balanced perspective of the person that helped shape the policies during their presidency.

In late August, I had the pleasure of returning to the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library with a friend who was visiting from Brooklyn and hadn’t been to any presidential library. Here is what we learned about Herbert Hoover: Hoover was a Republican and the 31st President of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933, during the Great Depression. Before that though, he was a statesman and engineer, and his background in mining and geology helped shape the conservation policies of the time: water and air pollution, land use, wildlife preservation, and… hey these are the same problems we still face today! I thought it might be good to look at how these issues were dealt with almost 100 years ago, because those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

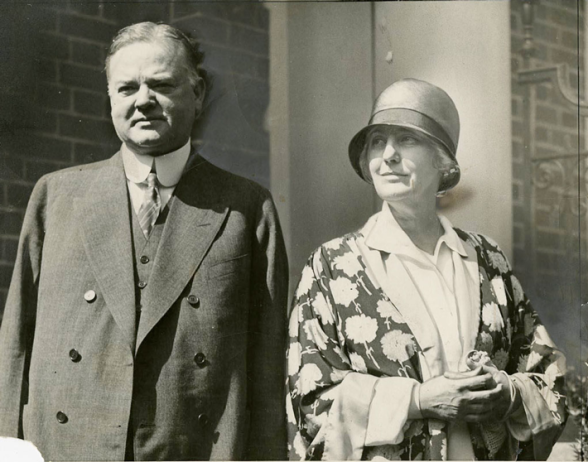

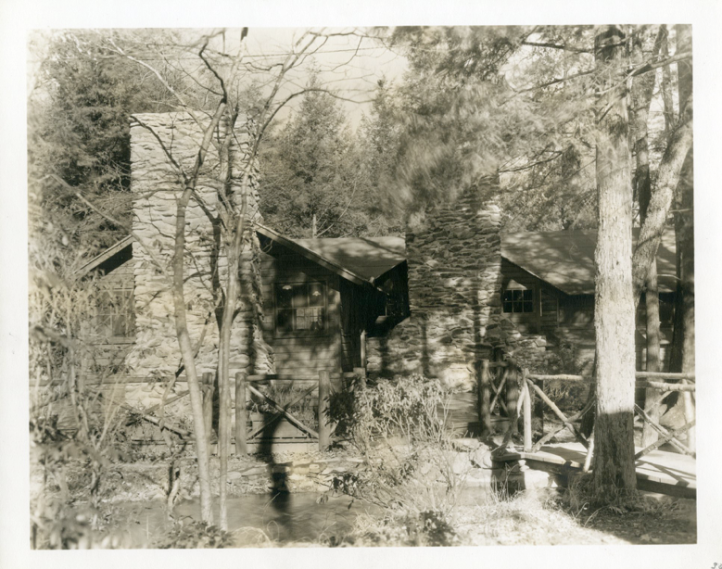

The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum is located at Hoover’s birthplace in West Branch, Iowa, only a ten-minute drive from The University of Iowa where I am a post-doctoral researcher. The grounds outside are beautiful and Hoover and his wife Lou Henry Hoover are interred at the top of a small hill, surrounded by manicured bushes and beyond that, prairie.

When you enter the library, there’s a small movie theatre and rooms to visit for exhibits that contain the Hoovers’ personal possessions. The main exhibit, “Tallgrass to Knee High: A Century of Iowa Farming,” details how farming practices had changed in the Midwest over the century before Hoover took office. It’s a great exhibit, and the timelines are filled with many photos and reprinted newspaper headlines from the turn of the 20th century. One neat thing about the exhibit is the interactive displays (and toys!) for children to use to learn about agriculture.

Surprisingly, only a small portion of the exhibit is devoted to Hoover himself and the role that he played as an engineer that became President, and this got me to think, “How did Hoover think about sustainability and agriculture nearly a century ago, and how did his background as an engineer shape the policies of his presidency?”

When I posed this question to the volunteers in the gift shop they called over to the archives and within five minutes we were back in the actual library. We had a chance to hold a piece of history in our hands: Hoover’s inauguration speech, complete with his own handwritten notes. Then we got to hold his wife Lou’s speech to the International Mining and Metallurgical Society, for which the Hoovers were awarded the society’s Gold Medal. And then we saw the books. Thousands of books devoted to all the presidents. One in particular caught my eye: Hoover, Conservation, and Consumerism: Engineering the Good Life by K. A. Clements, which I immediately ordered from Amazon.com when we returned home.

Here is what I’ve learned about Hoover’s life, and how it shaped his decision-making as President: Hoover was born in Iowa in 1875, but after his parents passed away he was relocated to live with family in Oregon. There he grew up Quaker and gained an appreciation for wilderness. He spent as much time outdoors as he could, and particularly enjoyed fishing. At age 16 he was part of the first class at Stanford University and earned a degree in engineering. While at Stanford, he met his wife Lou Henry, and after graduation they traveled the world. Hoover made a small fortune as a mining engineer in places like Western Australia and China, and he specialized in revitalizing failing mining operations.

The Hoovers translated the 16th century De re metallica from Latin to English for modern metallurgists, which I find immensely cool as a materials chemist. How many presidents, let alone people, do you know that can do that? Or this: Hoover organized humanitarian relief in Europe in the wake of World War I. In 1917, he was appointed as U.S. Food Administrator and told the Senate that one of his goals was “to centralize ideas and decentralize execution.” He believed that voluntary individual participation at the local level would firm up larger programs set up by the government. Could this be the origins of the “think globally, act locally” slogan embraced by environmentalists today?

When Hoover became Secretary of Commerce in 1920, a quote from his memoirs on this topic was particularly prescient: “the more men of engineering background who become public officials, the better for representative government.”

His thoughts on what benefits he saw engineers bringing to the public can be summarized in the following quote1:

It is a great profession. There is the fascination of watching a figment of the imagination emerge through the aid of science to a plan on paper. Then it moves to realization in stone or metal or energy. Then it brings jobs and homes to men. Then it elevates the standards of living and adds to the comforts of life. That is the engineer’s high privilege.

It’s clear that Hoover saw how his profession could benefit society, but there’s more to the story than that. He was an engineer who enjoyed nature, but he was also concerned with growing the economy. Moreover, Hoover rose to political prominence during a time when consumerism was pervading US society, and many people started to have free time for leisure.

This is where his views on conservation policy get a little hard to categorize. On one hand, his policies could be considered a natural extension of the Progressive agenda in that conservation was the planned development of all natural resources. On the other hand, he promoted human health and well-being as a balanced life that included nature and outdoor recreation. On yet another hand, his engineering background allowed him to synthesize ideas and prototypes from potentially disparate sources, and this was key to his policies on conservation and sustainability.

Hoover argued that his ideas about conservation, specifically rational planning and standardization, would lead to efficient production, cost cuts, and increased profits. These efficiencies would lead to more time for people to spend outdoors… but in an ever-decreasing amount of efficiently-harvested nature? It’s an argument that reads like the plot of Inception and boils down to proposing that the U.S. use natural resources to the fullest extent possible, but only until we couldn’t efficiently exploit mother nature anymore. Yikes! One example here would be his oil pollution policies. He said the US government should cap pollution with federal limits because pollution is wasteful, but not because it endangered wildlife. Protecting the environment was viewed as an unintentional benefit, which is surprising for someone who appreciated the wilderness and its benefits for human health and wellness.

Regardless of his motivations, Hoover pioneered some of the government’s first environmental policies, and his thoughts and ways of organizing and running meetings are still used today. For example, in discussions of how to protect the environment (without ruining the economy!), he would invite a diverse group of scholars, business leaders, farmers, etc. together to discuss environmental policies and present their various viewpoints. These meetings took place as organized national conferences on outdoor recreation where urban planners and wilderness advocates were brought together to plan how best to use natural spaces.

The conservation policy discussions were a mix of leisure, sustainability and economics, since Hoover believed that people should work hard but also partake in regular outdoor activities to both take breaks from industry and be mindful of natural resources. This could be viewed as a successful example of how people with very different end goals worked together to solve problems on a national level. Hoover’s conservation policies ultimately resulted in an expansion of the National Park system. Hoover is also credited as “the great engineer whose vision and persistence” made the construction of the Hoover Dam, which is still in use today, possible. For further reading on this technological marvel I’d suggest Building Hoover Dam: An Oral History of the Great Depression by Dunar and McBride.

In total, Hoover was able to use his experience and training as an engineer to execute policies and oversee conversations that are still of importance today. These are the types of long-lasting effects that one can have on the US if presidents or other local officials are engineers or scientists!

REFERENCES

- Petroski, H. Engineering: A Great Profession. American Scientist. 2006, 94(4) 304-307. JSTOR www.jstor.org/stable/27858794

If you’re interested in learning more about Presidential Libraries, visit https://www.archives.gov/presidential-libraries/visit and plan a trip to see some of the amazing exhibits soon!