A Biologist and a Chemist Walk into a Lab…then they have to share space and tools and work together…(you thought that was going to be a joke, right?)

Let me preface my opinion on this matter by putting it out there: I am a biologist. I work, however, in a chemistry laboratory. I am also married to a chemist, who is absolutely perfect in every way, except that she refers to every virus, bacterium, insect, spider, and even (affectionately) our cat as a ‘bug’. As a biologist, this is really annoying. Biological labels matter.

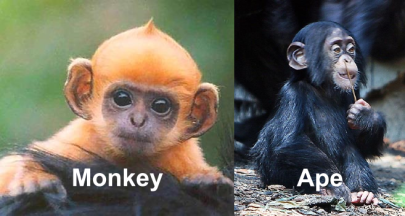

Consider apes and monkeys, two primates people often confuse. From their bodies to their DNA, apes are fundamentally different from monkeys. The notion of using one in place of the other is delightfully humorous but at the same time turns the field of primatology on its head. Likewise, I rely on my chemistry colleagues to keep me apprised of the many customs and conventions in chemistry that are foreign to me.

To the casual observer, it may seem that all scientists are the same. After all, we have the Scientific Method, not the Biology Method or the Chemistry Method or the Engineering Method, right?

Wrong. Well, sort of wrong and sort of right, like pretty much everything else in science. In reality, though they do indeed share the scientific method, there can still be as much drama between scientific subdisciplines as there is in Season 4 of Breaking Bad.

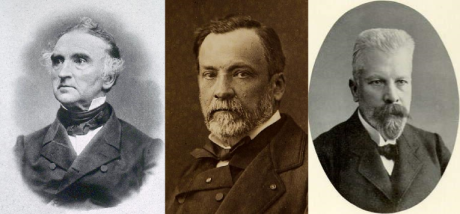

Consider the chemists and biologists of yore, whose efforts were focused, naturally, on determining how alcohol was made. In 1997 Arthur Kornberg described one of the most famous and long-running scientific feuds. In the mid-1800s, chemist-turned-biologist Louis Pasteur insisted that a live yeast cell was necessary for the production of alcohol while the German chemist Justus von Liebig was certain that there was a chemical process that occurred independently of yeast cells. After 30 years of bickering, this conflict was eventually resolved by another German chemist with training in biology, Eduard Büchner. This resolution occurred only by accident and was not helped by the vitriol on both sides. Büchner determined that fermentation could occur both inside and outside of yeast cells but does require a chemical that yeast cells produced—so in the end, both sides had a point.

At the time of this feud, the buildings, tools, and equipment of biologists and chemists were entirely separate. Today, these fields are more integrated. Remember, I’m a biologist working in a chemistry lab—this is not uncommon these days.

However, just putting us in the same lab doesn’t make us think about or approach our experiments in the same way. Biologists usually study systems that are messy, constantly changing and can only be probed by making measurements that indirectly reveal information about their finicky cells, tissues, or animals. The heart and soul of much chemistry research, meanwhile, is found in making very precise measurements of things like molecules, nanoparticles, or chemical processes—none of which are prone to reproduction or death, as in biology.

As evidenced by the alcohol production feud, the fields of chemistry and biology actually overlap inextricably, particularly in areas that affect human and environmental health (like nanoscience). The intermingling of chemistry and biology and their respective traditions is important in part because the ways scientists think about problems can affect how we decide to solve them. Even though we strive for objectivity, our backgrounds change how we do our jobs. On our best days, scientists are still just people with superstitions and bad habits passed down from our advisors and labmates. Ultimately, this can affect the conclusions that we draw about the problems we are studying, just as it did in the alcohol feud.

For me, it’s comfortable and easy to work with other biologists. They think like I do, use the same jargon, and get my jokes. There can be discomfort however at the boundaries between disciplines, but today that’s where many of the big discoveries are being made. While working in a chemistry lab, I’ve found it’s rewarding to work with people who approach problems completely differently from me. At the Center for Sustainable Nanotechology, we are getting comfortable with the discomfort of working across the fields of analytical chemistry, microbiology, physical chemistry, genetics, and materials science. We biologists in the Center have even trained a few of the chemists to stop calling everything ‘bugs’. Luckily there have been no big feuds yet, and we’re hot on the trail of some exciting discoveries. By working together, we are trying to think bigger about nanoscience.

Nice post! An interesting book to read, when science and the arts were not so far apart:

Richard Holmes’ “The Age of Wonder”. It has a fair amount of early chemistry and physics! -CJMurphy

great post!

Love this!—-R.Klaper